Last weekend, my kids and I built a scale model of the solar system!

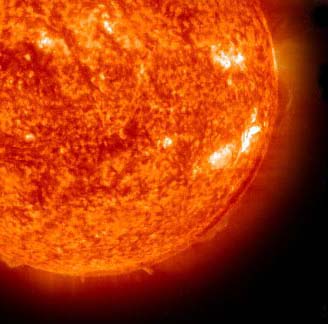

A lot of people don't realize that most of the models we grew up with in science class and the pictures we see of the solar system on

TV aren't shown to uniform scale. They generally present the planets in one scale, while their orbits are given a different scale.

Why is this? We were about to find out...

A Matter of Scale

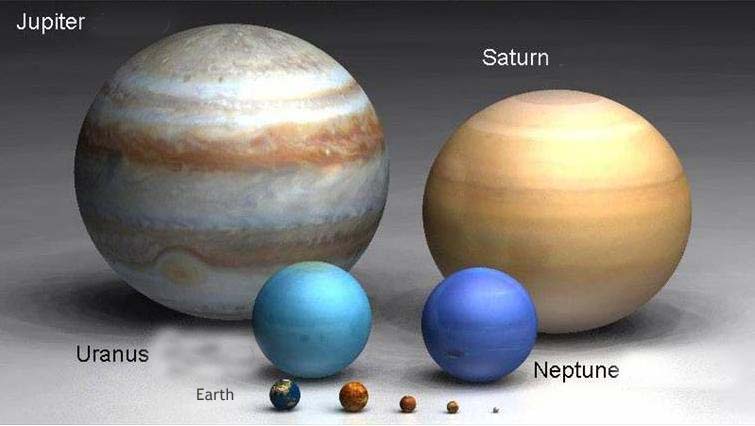

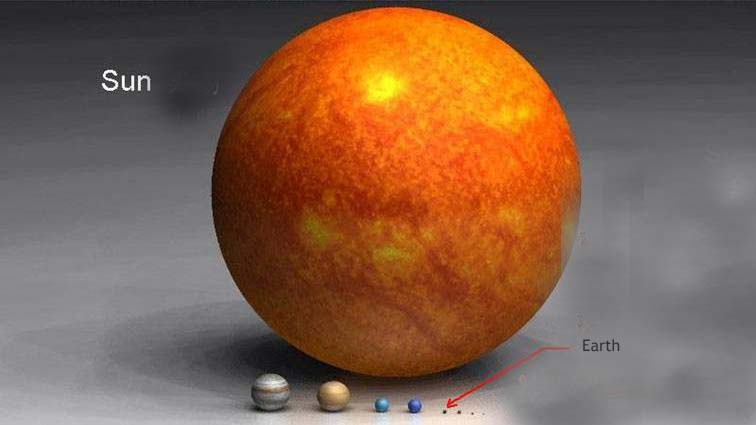

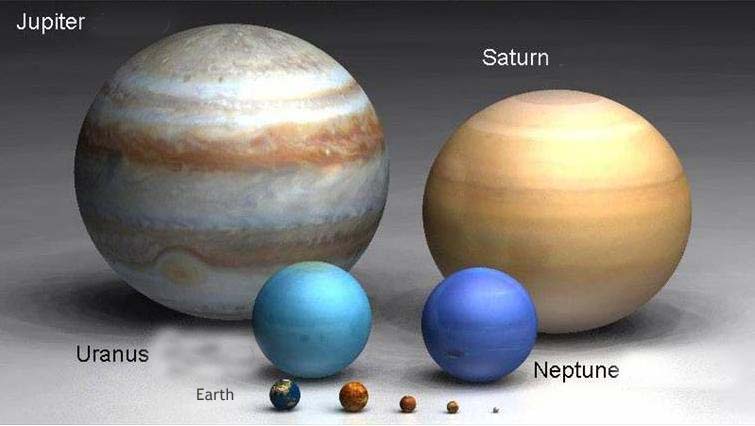

Above, you can see the relative sizes of the planets. The small planets along the bottom, in order, are Earth, Venus,

Mars, Mercury and Pluto.

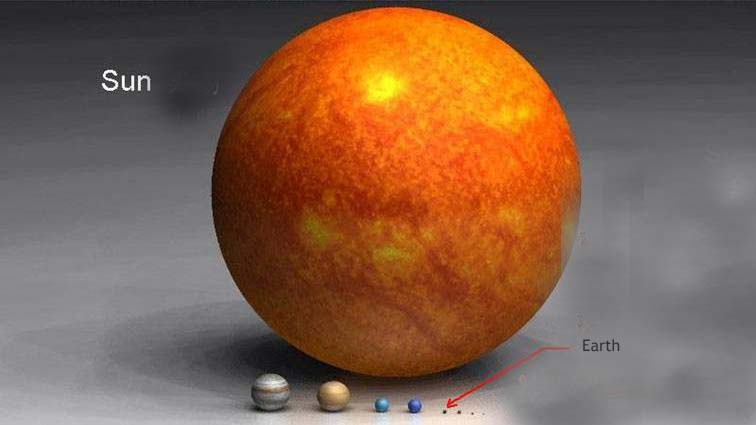

Now look at the planets next to the Sun! Pluto isn't even visible in this picture...

As I began to think about the planet sizes for our model, I initially thought that maybe we could have a section of our house stand in for the

Sun so the planets would be large enough to work with. It was time to bust out the calculator! Figuring for a "Sun" about 50 feet

across makes for a Pluto of about 1 inch wide and an Earth around 5-and-a-half inches. Good sizes to carry around, I figured. Looking good!

Let's check the size of Jupiter. Whoops, Jupiter comes out around 60 inches in diameter at this scale. That's too big, I realized, and did

a nervous check of Pluto's orbit to see how far we would need to walk. The answer surprised me. At the scale of a 50-foot Sun,

the orbit of Pluto is almost 40 miles away!

Back to the drawing board. I was beginning to see why models of the solar system use two different scales for planets and orbits —

but not us! We're out for real learning here, even if it is impractical.

I started to look for a much smaller Sun. We happened to have a fluorescent, slightly under-inflated, child-size soccer ball roughly

8-and-a-half inches across. A quick check of Pluto's orbit produced a distance of just over a thousand yards or a bit more than a

half-mile. Referring again to the picture of the relative sizes of the planets compared to the Sun, I realized the planets would indeed need to

be quite small.

I also began to realize it was going to be something of a stretch to get the kids to walk more than a half-mile in the Virginia summer

heat. But real learning isn't always a comfortable walk in the park. We had our Sun!

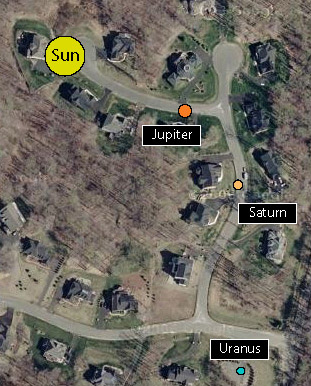

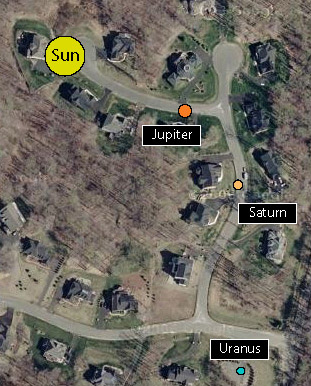

Luckily, we live on a cul-de-sac at the end of a pretty quiet road in the back corner of a community with no real traffic to speak of.

Pacing out planetary orbits to a thousand yards just might work out after all. Next it was time to work out the sizes of the planets at

our 8-and-a-half-inch Sun scale.

Peppercorn Earth

Okay! Sharp pencils and Internet astronomical resources gave way to a few interesting observations.

At this scale, Mercury is less than three-quarters of a millimeter across or about the size of a candy sprinkle. I imagined trying to find

a candy sprinkle in the vast asphalt expanse of the road before realizing that not only are candy sprinkles the right size,

they are also disposable.

A quick rummaging through the pantry produced a Fourth-of-July-themed candy shaker and I chose a red sprinkle to represent hot Mercury.

I have been told that since I am attempting to achieve real learning, I should point out that these small, round pellets of sugar

are actually an ancient form of candy called

nonpareils. I have

determined that culinary people are much worse than computer science people in regard to

using proper terminology.

Next up were Venus and Earth, each right around two millimeters in diameter. Still thinking disposable, it was time to raid the spice

cabinet. The "Gourmet Peppercorn Mix" produced a variety of both colors and sizes to choose from. Peppercorn Earth is slightly

larger (and a little greener) than Peppercorn Venus.

With Mars sizing up at only one millimeter, I knew was going to have to change spices. Luckily, rummaging through the spice

cabinet again produced astronomical value — an unopened vial of mustard seed. Now, I have never cooked with mustard seed, nor

do I know what culinary delight one might craft with mustard seeds (except, perhaps mustard), but using my keen power of

observation, I had stumbled on this useful factoid: mustard seeds are roughly one millimeter in diameter.

With Jupiter and Saturn, we are finally out of the realm of edible planets and have arrived at the macro-objects we can reasonably

expect to find on the street when we retrace our steps back from Pluto. In our model, Jupiter should be 22 millimeters wide, which

is a diameter of .85 inches or, as we say in the engineering world, "about an inch."

If you have kids, you undoubtedly have a large selection of SuperBalls hiding around the house that, in addition to having amazingly high

coefficients of restitution, are also about an inch in diameter.

Saturn gave me a little more trouble since, at 18 millimeters or .71 inches wide, they are smaller than SuperBalls, but larger that your

standard marble. I went with a marble of the shooter or "matris" variety, also found

around the house.

Uranus and Neptune are almost the same size, which is odd considering that one has a much funnier name than the other. At seven

millimeters in diameter, I was able to turn up a couple of ball bearings that did the trick nicely. I was getting a little nervous that one of

my kids would point out that none of the larger planets seem to look much like their astronomical counterparts, but I carried on.

Finally it came down to Pluto and another candy dot nonpareil, this time a blue one to represent the cold nether-regions of our solar system.

While I had the candy sprinkles nonpareils spilled out and rolling across the kitchen counter, I selected a white one to represent our own moon.

The Pacecraft Departs

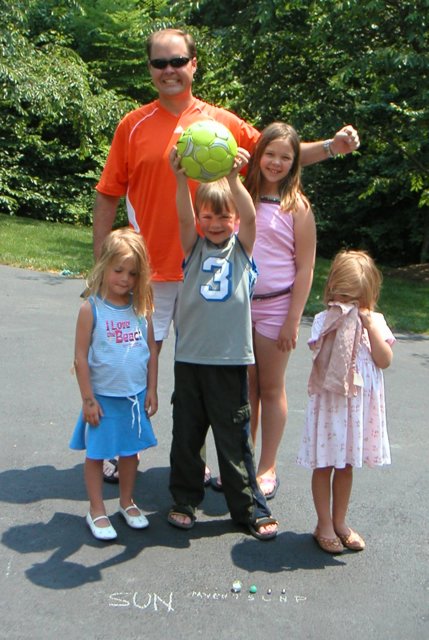

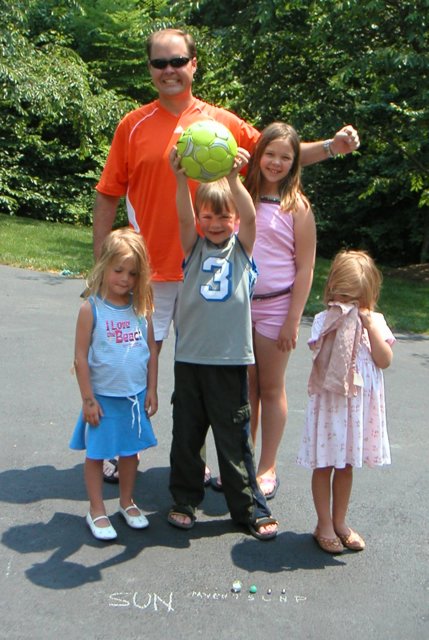

Finally it was solar system day! On a sunny and hot afternoon in June, I gathered the kids in the 90-degree heat of the driveway to go

over the mission specifics. We reviewed the various planetary bodies, removing them carefully one-by-one from their Ziploc cargo hold.

As we went over the various planet representations I had assembled, my son Mason pointed out that the real Mercury was actually a

LOT bigger than Pluto.

Mason is seven.

Mason did not seem at all swayed by the fact that, though I may have estimated the planet sizes a little, I had chosen a

slightly smaller than average candy Pluto and a slightly larger than average candy Mercury.

I also pointed out the colors — wasn't that clever?

"Dad, Mercury isn't red and Pluto isn't blue."

Assembled to the right is the full Mission Team.

Before setting out, we went over the mission assignments consisting of who was going to be in charge of carrying which planet. We

also went over a number of mission safety regulations, which amounted primarily to not dropping one's mission assignment onto the street

where we would never find it again. And watching for the occasional car.

My pace is around two-and-a-half feet so I had previously calculated all the solar orbits and jotted down on a card how many paces it

would be to each planet. We departed in our "Pace-craft" at precisely 32 minutes past the hour, in homage to the

Apollo 11 flight, and set out on the 12-pace walk to Mercury.

From Mercury, the Sun is still pretty big. That's my wife, Cindy, who we referred to as Director of Mission Control

(although she has made it clear that she prefers Sun Goddess or, alternately, The One Who Has to Pick Up After Everyone Around Here.)

Here we are in the cul-de-sac at Mercury looking back at the Sun. When we walk, we are traveling at almost thirty times the speed of

light, which moves at less than two inches-per-second at this scale. Onward another 10 paces to Venus.

From Venus, the Sun still appears a lot larger than it does from Earth. Another 8 paces to Earth for a total of 30 paces so far.

Here we are standing at Earth, just at the edge of the cul-de-sac.

From the scale Earth orbit, it is interesting to notice that the soccer ball appears exactly the same size as the real Sun does up in the sky.

Note that this is not a good thing to point out to children who may take the opportunity to look directly at the Sun to see if you really

know what you are talking about.

If your kids are older, you can try the relative size experiment by suggesting they hold an outstretched pinky up to the soccer ball and

compare its size (about half the pinky) to the size of an early evening Moon. Smaller kids will not understand why comparing the

size of the "Sun" to the size of the Moon is significant since clearly here at Peppercorn Earth, the moon is a candy dot and

they will presume you are trying to pull a fast one. I know this by experience.

Here's candy moon barely visible circling our Earth about two-and-a-half inches out.

Another 16 paces from Earth and the Sun is getting smaller. We're only about 40 yards from the soccer ball here at Mars and the kids

are pretty sure we'll be at Pluto before we hit the end of the 180-yard street.

Wow! What happened? There we are three-quarters of the way down the street now and only at Jupiter. It was another 112 paces

to Jupiter from Mars and we were now 158 paces, or around 130 yards from the Sun.

From Jupiter, you can barely even see the soccer ball Sun. More importantly, to the children anyway, it was looking like we would

need to turn the corner and continue down the road in order to wrap it up and head back to the air-conditioned comforts of Mission Control.

Indeed we did, for it was another 132 paces to Saturn and then another 294 paces to Uranus, which was

waaaaaaay over at the community pool.

To the parking lot of the community pool, we had already walked more than a quarter-mile and the kids were starting to notice a

potentially-unwelcome fact about the solar system, given the stifling heat: the distances we were walking to each new planet were

growing geometrically (except they used the term LOTS in place of "geometrically").

As the hot summer sun attempted to blind us by reflecting off of ball bearing Uranus, we made the bold decision to turn the pacecraft

around and head back to Mission Control immediately. Given that Uranus is almost exactly half-way to Pluto, it provided a fortunate

opportunity to envision exactly how far it would really be if we were to walk all the way out to Pluto, somewhere in the next county.

On the way back, after stopping to pick up Saturn and then walking another 38 paces to point out the where Neptune would be if we

were still walking in a straight line, we went over a few more interesting distances to consider at our scale, with which I will leave you.

The closest star to ours is Alpha Centauri. How far would we have to walk at our scale to reach it? The kids all agreed it would be

pretty far. One opined that it might be as far away as the highway (about 3 miles.)

Answer: Almost four-thousand miles

How far to the center of the Milky Way galaxy?

Twenty-five million miles

And to our sister galaxy, Andromeda?

Six billion miles